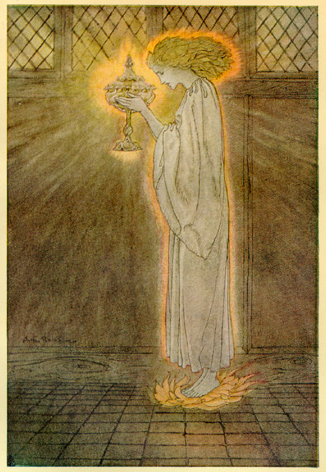

Jaime Lannister by Breogan

As discussed in Radio Westeros Episode 12

Artwork courtesy of Breogan

When Jaime Lannister arrives at Winterfell in Robert’s party, Ned recognizes him as the group arrives, but it is through Jon Snow’s eyes that we get our first description:

Ser Jaime Lannister was twin to Queen Cersei; tall and golden, with flashing green eyes and a smile that cut like a knife. He wore crimson silk, high black boots, a black satin cloak. On the breast of his tunic, the lion of his House was embroidered in gold thread, roaring its defiance. They called him the Lion of Lannister to his face and whispered “Kingslayer” behind his back. Jon found it hard to look away from him. This is what a king should look like, he thought to himself as the man passed.

The visual of the defiant lion on his breast turns out to be extremely apt for Jaime. His pride doesn’t allow him to justify the act that earned him the epithet of “Kingslayer,” and his defiance in the face of judgment is made plain later in ASoS when he relates the story of Aerys’s death and Ned Stark‘s discovery of him sitting on the Iron Throne to Brienne, ending with “By what right does the wolf judge the lion?” Here we see clearly the inner conflict that has been only hinted at and really defines his character.

If Jaime is first identified in Jon’s point of view as “the Kingslayer,” then it is from Bran that we learn a bit more about him:

Ser Jaime Lannister looked more like the knights in the stories, and he was of the Kingsguard too, but Robb said he had killed the old mad king and shouldn’t count anymore.

When Bran Stark chances upon Jaime’s assignation with his sister Cersei in a deserted tower at Winterfell, we see a man who is willing to do anything to hide his incestuous, adulterous relationship with the Queen

“The man looked over at the woman. ‘The things I do for love,’ he said with loathing. He gave Bran a shove.”

We have been set up to despise this character who slayed a king and crippled a little boy. As the story of Jaime Lannister unfolds, we get a picture of a man who is “‘restless, and quick to anger,’” as the Blackfish tells Robb, and who, in the words of Ned Stark, “swore a vow to protect his king’s life with his own, [and] then . . . opened that king’s throat with a sword.” Ser Barristan Selmy, in Bran Stark’s estimation “the greatest living knight,” calls Jaime “the false knight who profaned his blade with the blood of the king he had sworn to defend.” Combined with the ambush of Ned’s party in King’s Landing and Ned’s bitter memory of “Jaime Lannister’s smile, and Jory dead in his arms[,]” by the end of ACoK we have little reason to find any redeeming qualities in the man and can be forgiven for agreeing with Cat when she thinks:

“There is nothing here but arrogance and pride, and the empty courage of a madman. I am wasting my breath with this one. If there was ever a spark of honor in him, it is long dead.”

But there are a couple of small hints that his character might be more thana soiled knight and kingslayer who is willing to kill children to keep his incestuous relationship with his sister secret.

The first hint we get is from Tyrion, who thinks:

There was very little that Jaime took seriously. Tyrion knew that about his brother, and forgave it. During all the terrible long years of his childhood, only Jaime had ever shown him the smallest measure of affection or respect, and for that Tyrion was willing to forgive him most anything.

And then from the story about the deaths of Rickard and Brandon Stark that he tells Catelyn when he is in captivity at Riverrun in her final chapter in ACoK, we get one of the first hints that there may have been extenuating circumstances in the death of Aerys Targaryen. While Jaime is quick to deny that vengeance for the Starks had anything to do with his murder of the king, Martin has sown the seeds of doubt in our minds.

In that scene, when Catelyn accuses him of forsaking “every vow [he] ever swore,” we get this interesting rejoinder from Jaime:

So many vows . . . they make you swear and swear. Defend the king. Obey the king. Keep his secrets. Do his bidding. Your life for his. But obey your father. Love your sister. Protect the innocent. Defend the weak. Respect the gods. Obey the laws. It’s too much. No matter what you do, you’re forsaking one vow or the other.

Jaime’s defiance in the face of judgment seems to define him, right up to his meeting with Catelyn. He isn’t bothered to defend his honor by explaining his point of view even in the face of accusations of trying to kill a child. In fact, he may really believe that he has “shit for honor.”

At the same time, the small amount of trust that Catelyn has placed in him for the return of her daughters, and his journey through the Riverlands with Brienne have the effect of reminding him what honor can be, of his early ideals and, as we’ll see, may even inspire a faint hope of redemption.

It’s important to note here that Jaime realizes full well that Cat’s trust is more in Tyrion, as he thinks: “A strange woman, to trust her girls to a man with shit for honor. Though she was trusting him as little as she dared. She is putting her hope in Tyrion, not in me.” And of course, Cat has little enough reason to trust either of the Lannister brothers at this point in the story. But in spite of her disdain for this man who tried to take her child’s life and her clear understanding of the consequences of freeing him, Cat decides to send him to Tyrion in exchange for her daughters.

We learn in his first point-of-view chapter in ASoS that this decision involved a lot of vowing. In spite of his admitted conflicts with vows, Cat has decided to put her faith in Jaime’s vows made at swordpoint:

Swear that you will never again take up arms against Stark nor Tully. Swear that you will compel your brother to honor his pledge to return my daughters safe and unharmed. Swear on your honor as a knight, on your honor as a Lannister, on your honor as a Sworn Brother of the Kingsguard. Swear it by your sister’s life, and your father’s, and your son’s, by the old gods and the new, and I’ll send you back to your sister. Refuse, and I will have your blood.

As he is traveling the Riverlands with Brienne, who despises him for his crimes, we learn a few things about Jaime. When she asks, “Why did you take the oath? . . . Why don the white cloak if you meant to betray all it stood for?” his glib answer about his youth, meant as a shield to his true reasons, fails to satisfy her. But in his internal monologue he recalls the scheme by his sister that led to his investiture into the Kingsguard, Tywin’s resignation as Hand, and Cersei’s return to Casterly Rock. Jaime, it turns out, was taken in by that same villain that will snare Robb Stark— a teenage boy’s libido.

We also learn from that exchange with Brienne that he is fiercely proud of his knighthood, and how he earned it, telling her:

I earned [emphasis mine] my knighthood. Nothing was given to me. I won a tourney mêlée at thirteen, when I was yet a squire. At fifteen, I rode with Ser Arthur Dayne against the Kingswood Brotherhood, and he knighted me on the battlefield. It was that white cloak that soiled me, not the other way around [emphasis mine].

We learn later that Jaime had quickly realized why he had been chosen for the Kingsguard. The journey through the Riverlands provokes many memories of the year of the False Spring, and he thinks:

“Aerys had chosen him to spite his father, to rob Lord Tywin of his heir. Even now, all these years later, the thought was bitter.”

He was resentful of his position right from the start, and as he tells Brienne, “Aerys liked to keep me close. I was my father’s son, so he did not trust me.” So it seems that not only was he judged untrustworthy, but also that he was denied the opportunity to be a true knight and restricted mainly to being a glorified bodyguard for the royal family. Which, for a young man who had dreamed of the glories of knighthood, might be enough reason to be resentful. As we’ll see, there is more than restriction in play with his service to Aerys, when the conflicting vows he alluded to with Catelyn become a driving force in his arc.

Jaime told Cat, “So many vows . . . they make you swear and swear[,]” and then went on to sum up both his kingsguard vows and his knightly vows, ending with “No matter what you do, you’re forsaking one vow or the other.” We have a sense by now that there was some service required of him as a Kingsguard that was in conflict with his knightly vows, and, furthermore, that he is angry about it.

When we discover the full story, it becomes obvious that “Protect the innocent. Defend the weak. Respect the gods. Obey the laws” may have been all but impossible whilst doing the bidding of the mad king. Not only did the king want to burn thousands of innocents in King’s Landing as the rebellion bore down upon him, but we also learn in bits and pieces about other, smaller things that would have been conflicting to support, like Aerys murdering the Starks and their bannermen, burning Lord Chelsted, raping his own wife, and refusing to let his daughter-in-law and grandchildren seek safety with Rhaella and Viserys.

Jaime recalls Gerold Hightower telling him, “You swore a vow to guard the king, not to judge him.” But all told, turning a blind eye may have become commonplace during the months Jaime stood guard for Aerys, and for someone who was arguably an idealistic young knight it is perhaps no wonder that he reached a breaking point in which he chose his knightly vows over the Kingsguard vow.

By the time of his journey with Brienne, however, he has a somewhat jaded view of knights. When they come across an oak tree full of dead women, the idealistic Brienne says, “No true knight would condone such wanton butchery.” Jaime’s reply, True knights see worse every time they ride to war, wench . . . . And do worse, yes[,]” is highly reminiscent of Sandor Clegane’s comment to the Brotherhood without Banners: “Might be you are knights after all. You lie like knights, maybe you murder like knights.”

This is an interesting parallel if you consider that the only two people named as “false knights” in the series are Jaime Lannister and Sandor’s brother, Gregor Clegane, the implication being that these men have so badly broken their vows that they are beyond the redemption that even “true knights” may seek. Ironically, the two characters most often seen in contrast to Jaime and Gregor are Brienne and Sandor, neither of whom are knights, but both of whom show some of the qualities a “true knight” is expected to have. In contrast to Ser Gregor, though, Jaime embarks on a redemption arc early on in ASoS.

We get a first hint of a redemptive story just before he and Brienne are taken by the Brave Companions, when Jaime thinks:

[He] had decided that he would return Sansa, and the younger girl as well if she could be found. It was not like to win him back his lost honor, but the notion of keeping faith when they all expected betrayal amused him more than he could say.

The arc accelerates with the loss of his hand, the “sapphires” incident, in which he cleverly helps Brienne avoid rape, and his rescue of Brienne from the bear pit. All of these really demarcate his journey from false knight to redeemed soul.

Up to the point where he loses his hand to the Brave Companions, Jaime has maintained his usual defiance and bravado, offering bribes to the sellswords just moments before the amputation. This doesn’t get him far, as Urswyck tells him, “I have heard enough, Kingslayer. I would have to be a great fool indeed to believe the promises of an oathbreaker like you[,]” which provokes a chill of fear in Jaime and some familiar resentment as well — “Aerys . . .. It always turns on Aerys.”

With the loss of his hand, Jaime experiences more than a little bit of despair, his certainties all swept away, and even at one point telling Brienne that he’s dying. Remember his views on “cripples” that he expressed when Bran Stark lay paralyzed:

“Even if the boy does live, he will be a cripple. Worse than a cripple. A grotesque. Give me a good clean death.”

Though this didn’t exactly sit well with Tyrion, it goes a long way towards explaining Jaime’s despair when he finds himself to be a self-described cripple. When he tells Brienne he’s giving up, she goads him with the reply “Are you so craven?” Jaime thinks of all the things men have called him— oathbreaker, liar, murderer, cruel, treacherous, reckless— but never craven. It’s almost like she has laid down the gauntlet of identity crisis there, but still his reply to her is only “What else can I do but die?”

Brienne tells him to live— live to fight and take revenge, and he takes the challenge to heart, thinking not long after:

Live . . . live for Cersei, live for Tyrion. Live for vengeance. A Lannister always pays his debts. . . . When I reach King’s Landing I’ll have a new hand forged, a golden hand, and one day I’ll use it to rip out Vargo Hoat’s throat.

But this is really only the beginning for Jaime, since the loss of his right hand is so shattering to his identity. The loss of his sword hand leads him to think:

. . . without it he was nothing. The other was no good to him. Since the time he could walk, his left arm had been his shield arm, no more. It was his right hand that made him a knight; his right arm that made him a man.

But the poetic justice of the loss isn’t lost on him. As he tells Brienne, “I’ve lost the hand I killed the king with. The hand that flung the Stark boy from that tower. The hand I’d slide between my sister’s thighs to make her wet.” His identity crisis is spelled right out for us in his point of view when he thinks, “The goat had robbed him of his glory and his shame, both at once. Leaving what? Who am I now?”

The scene in the Harrenhal bathhouse, where he opens up to Brienne about the real reason he killed Aerys Targaryen, begins to answer that question and makes the reader sit up and take notice that this man might not be only a vicious and self-interested killer. In this instance at least, he just might be an unsung hero.

During this part of Jaime’s arc he has become progressively more and more filthy. Described as unwashed, unshaven and “wasted” after his imprisonment at Riverrun, Jaime shaves his head after they leave. But after their capture by the Mummers, he becomes positively filthy, described as having vomited on and soiled himself, coated in grime, blood and pus, and wearing his rotting hand around his throat.

This could be seen as a statement on the iconic “soiled knight.” Not only is Jaime literally filthy and soiled, but he is also wearing the symbol of his shame around his neck— a grim, rotting reminder for all the world to see. In the bathhouse at Harrenhal, he appears as Brienne is in the bath and climbs in with her in a way that seems designed to disquiet her. As he sits there and begins to wash, “the water darken[s] as the caked dirt dissolve[s] off his skin.” Jaime is cleansing himself for the first time in months, and he and Brienne begin to exchange their typical barbed comments. But as the dirt dissolves, Jaime finds himself telling Brienne exactly what happened that day in King’s Landing, with Ned Stark bearing down upon the city and his own father at the gates. Finally both Brienne and the reader learn what has been behind all of his cryptic comments about the murder of Aerys and his conflicting vows. At the end, in the face of Brienne’s disbelief at the ending of his story (“If this is true, how is it no one knows?”), he replies, “The knights of the Kingsguard are sworn to keep the king’s secrets. Would you have me break my oath?” This statement emphasizes the dilemma he faced in King’s Landing. On the other hand, his symbolic cleansing of his shame by finally confessing the truth of it to another human being — significantly, Brienne — is the reason the bathhouse is the perfect place for Jaime to earn some redemption, both from the reader and Brienne. George has washed away some of that grime from a knight who has been portrayed as soiled since early in the story.

However, as shown by his “By what right does the wolf judge the lion?” comment to Brienne his inner rage at being judged is profound. By the time he reaches King’s Landing with Brienne, we see that it hasn’t fully abated. When Loras Tyrell demands that Brienne be held accountable for the death of Renly Baratheon and threatens her with his naked blade, Jaime orders her to be held in a tower room for her own safety. But “Brienne’s big blue eyes [are] full of hurt” as she is led away, and he thinks to himself “Why must they misunderstand every bloody thing he did [emphasis mine]?” This really underlines his continued frustration with this theme, which has plagued him since Aerys chose him for the Kingsguard.

In his anger at remembering Ned Stark’s judgment, Jaime suffers an awkward fall in the bath. Brienne catches him, causing him to think of her as “[g]entler than Cersei.” He hears her shouting to the guards for the help, calling out “The Kingslayer!” In a moment that highlights the theme of names that follows both Jaime and Brienne, he says to her:

“Jaime . . . my name is Jaime.”

Later when they dine with Roose Bolton, they are brought up to date on what has been happening with the Starks, Freys and Lannisters while they’ve been traveling. Roose speaks cryptically about the prospects of King Robb, telling them about the Karstarks, Duskendale and the upcoming wedding at the Twins. The overall tone is quite menacing, though the result of the interview with Roose is an agreement that Jaime will absolve him of any responsibility for his maiming. Brienne is informed that Arya Stark is in custody and will be “returned . . . to the north[,]” while Sansa has been married to the Imp. When she stubbornly repeats her mission from Catelyn to deliver Jaime in exchange for the girls, she is told,“Ser Jaime will continue on to King’s Landing. I said nothing about you, I fear. It would be unconscionable of me to deprive Lord Vargo of both his prizes. . . . Were I you, my lady, I should worry less about Starks and rather more about sapphires.”

Shortly after, Jaime sets out on the road to King’s Landing in the company of Steelshanks Walton, Qyburn, and two hundred men. He’s looking ahead to Cersei and has only a momentary pang at leaving Brienne behind, even when he’s told by Qyburn that the sapphire-less ransom offered by her father pretty much assures that she’ll be raped and abused by the Mummers. He resolves to think no more about her, which lasts until he falls asleep with his head on a weirwood stump and has a remarkable dream.

He’s naked, beneath Casterly Rock, and his hand is whole. He is forced at spearpoint into a watery cavern, where his sister and father and other family members appear and tell him he is in “[his] place . . . [his] darkness.” Then he finds himself alone in the darkness with a sword, lit with blue flame; when the flame goes out, he hears Cersei say, he will die.

But he’s not alone for long, because into his darkness appears Brienne, naked as well and bound, but still stubbornly declaring her oath and obligation to keep him safe. He cuts her bonds, and suddenly she has a flaming sword as well, and he thinks, “In this light she could almost be a beauty . . .. In this light she could almost be a knight.”

This is where things get weird. Jaime hears a horse approaching, and for a moment he is reminded of Ned Stark judging him in the throne room at King’s Landing after Aerys’ death. But itis Rhaegar Targaryen and Jaime’s Kingsguard brothers who appear and accuse him of breaking his vows. He tries to tell them how it happened to justify himself, but his sword’s flame goes out, leaving only Brienne to protect him, and his ghosts come rushing in.

When he wakes screaming, he notices the stump is made of weirwood, which reminds him again of Ned Stark, and he has an odd thought: “It was not him . . . . It was never him.” While he could simply be thinking of his dream, this might actually be more symbolic. Jaime has spent the last fifteen years judging himself, just as much as anyone else has done. His anger has been directed as much at himself as at Ned Stark, but Brienne has had a profound effect upon him. With her stubborn loyalty to Catelyn and her vows, he’s seen what idealism and chivalry can mean, and that it’s possible to save and protect a person even if you have no personal interest in doing so.

And so he turns the train around. Using a combination of threats and bribes he convinces Walton to bring the entire group back where they came from. He tells Walton, “I left something at Harrenhal.” When he arrives, his rescue of Brienne from both the bear and Bloody Mummers is not only the reason Brienne is now indebted to Jaime Lannister for her very life but also a highly symbolic rescue of a maiden by a white knight. When she asks him why he returned (using his proper name, by the way) he simply tells her, “I dreamed of you[.]”

When Jaime is ultimately reunited with his family, it’s made very clear that his journey in the Riverlands has changed him in a fundamental way. He still has the bitterness that comes from being continually misjudged, but we get little hints like the thought he has when reflecting about Joffrey’s death (“Jaime was sick of lies.”) and Cersei’s remark to him (“you’re changed.”).

He quarrels with Tywin over the notion of duty when he hears of Tywin’s scheme to marry him to Margaery Tyrell and Cersei to Oberyn Martell. Tywin commands Jaime to forsake the Kingsguard, which he had stuck with all of these years in spite of his disillusion and dishonor. We learned in ASoS that when he realised the reasons Aerys chose him,“[h]e would have ripped the cloak off then and there if he could have, but it was too late. He had said the words whilst half the realm looked on, and a Kingsguard served for life [emphasis mine].”

It seems that in spite of his reputation, he takes the Kingsguard rather seriously, and when Tywin tells Jaime what is expected of him, in that purely Tywin-esque way that brooks no opposition, he refuses:

“NO!” Jaime had heard all that he could stand. No, more than he could stand. He was sick of it, sick of lords and lies, sick of his father, his sister, sick of the whole bloody business. “No. No. No. No. No. How many times must I say no before you’ll hear it?

. . .

I am a knight of the Kingsguard. The Lord Commander of the Kingsguard! And that’s all I mean to be [emphasis mine]!”

This ends with Tywin telling him, “You are not my son. . . . You say you are the Lord Commander of the Kingsguard, and only that. Very well, ser. Go do your duty.”

For seemingly the first time in his adult life, Jaime has turned his back on his duty to House Lannister in favor of a path that must seem to him to be more honorable. This continues when he later refuses to have sex with Cersei in the White Tower and ultimately ends up freeing his brother Tyrion from the black cells.

His inner monologue shows his increasing disillusionment with Cersei, which begins with his refusal to bed her in the White Tower and is furthered by Tyrion’s “Lancel and Osmund Kettleblack and probably Moon Boy for all I know” line. The fracturing of Jaime and Cersei’s fabled union is critical to his redemption arc and culminates at Riverrun, when he burns the letter she sends him from her imprisonment and turns his back on her in favor of his commitment to resolve the Riverlands situation peacefully. His travels in the Riverlands in AFfC underscore that he is not only resolved to bring matters there to a conclusion as peacefully as possible, but also that he is determined to keep his vow to Cat to “never again take up arms against Stark nor Tully.”

But before we arrive at the final scenes that illustrate his transformation from “the Kingslayer” to a man of honor, let’s return to King’s Landing and two key scenes there that really highlight his redemptive arc. First is his review of the White Book of the Kingsguard. He thinks his deeds recorded on the pages there are rather “scant and mingy” and finds himself recalling the lost days of his youth, before dishonor had changed him. When he thinks of his dead Kingsguard brothers he wonders:

And me, that boy I was . . . when did he die, I wonder? When I donned the white cloak? When I opened Aerys’s throat? That boy had wanted to be Ser Arthur Dayne, but someplace along the way he had become the Smiling Knight instead.

His musing over the White Book culminates when he has Brienne summoned to him and sends her off on a quest to “make good our stupid vows to your precious dead Lady Catelyn[.]” He gives her the sword Oathkeeper and tells her she’ll be “defending Ned Stark’s daughter with Ned Stark’s own steel[.]” He also tells Brienne, “I have made kings and unmade them. Sansa Stark is my last chance for honor [emphasis mine].” Then, in spite of a moment of misunderstanding that really irks Jaime, Brienne promises to “find the girl and keep her safe. For her lady mother’s sake. And for yours.”

Jaime’s narrative with the White Book comes to a close when he records the truth of his movements during the War of the Five Kings and viewing the blank page that remains — the very embodiment of a “tabula rasa” — thinks:

“He could write whatever he chose, henceforth. Whatever he chose . . .”

So it seems like Jaime has chosen the path of honor, setting in motion a hoped-for rescue that could not only injure his House, but also, if he believes the accusations of his sister, allow his son’s murderer to go free. It’s really made plain here that Jaime has developed a keen appreciation for Brienne of Tarth. He has even made a point of using her proper name, and written about her delivering him safely to King’s Landing in the White Book.

During his mission in the Riverlands he has a rather forceful exchange with Red Ronnet Connington at Harrenhal, where he not only insists that Ronnet use her proper name and title, but also knocks him down with his golden hand. Red Ronnet was really disrespectful of Brienne, and Jaime took issue with it. After slugging him in the face with the golden hand, he tells Ronnet,

“You are speaking of a highborn lady, ser. Call her by her name. Call her Brienne.”

This moment of defending Brienne marks the huge change in Jaime. He himself has belittled her and failed to use her proper name. But he has taken on board the similarities he and Brienne have, from their hated nicknames to the reputations they had had to bear, and has gained an appreciation and respect for Brienne as a person. Which is probably why it comes as no surprise that when Brienne finds him encamped at Pennytree some time later and begs him to come with her because she’s found the girl “but [he] will need to come alone[,] elsewise, the Hound will kill her[,]” he apparently leaves alone with her with no hesitation.

Whether Jaime’s redemption arc results in tragedy or triumph remains to be seen, but his departure with Brienne speaks volumes about the choices he’s made as his arc progresses in AFfC.